White supremacy is not confined to strange men in the Deep South who put on white cloaks, it is not confined to strange gatherings of the English Defence League. – David Lammy

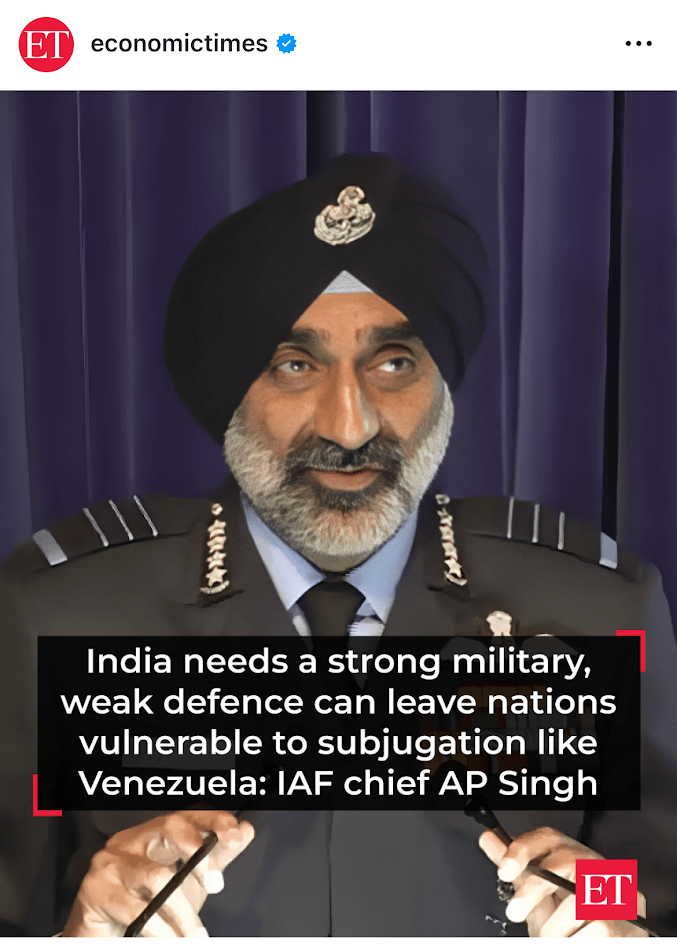

When Indian Air Force Chief Air Chief Marshal AP Singh recently stated that “India needs a strong military, weak defence can leave nations vulnerable to subjugation,” he was speaking from a position of regional security concerns. But his words carry a profound resonance that extends far beyond South Asia’s geopolitical landscape. For African Americans, a community with a centuries-long history of fighting for autonomy, dignity, and self-determination, this statement offers crucial lessons about the relationship between strength, vulnerability, and freedom.

The African American experience in the United States has been fundamentally shaped by periods of vulnerability and the absence of adequate means of self-defense. From the horrors of chattel slavery through Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and into the modern era, Black communities have repeatedly faced the consequences of being unable to fully protect themselves from subjugation, violence, and exploitation. During slavery, the systematic disarmament of enslaved peoples was a cornerstone of the institution’s survival. Laws throughout the South explicitly prohibited Black people from owning firearms or weapons, understanding that an armed population could resist bondage. This wasn’t merely about physical weapons—it extended to literacy, organization, and any form of power that might enable resistance or self-determination.

The pattern continued after emancipation. During Reconstruction, Black militias and armed self-defense groups proved essential to protecting newly won freedoms. However, once federal troops withdrew from the South and white supremacist forces regained control, systematic disarmament and the crushing of Black political and economic power led directly to the subjugation of Jim Crow—a subjugation that would last nearly a century. This historical arc demonstrates precisely what Chief Marshal Singh warned about: when communities lack the means to defend themselves, they become vulnerable to forces that would subjugate them.

While the IAF chief was speaking specifically about military capacity, the principle applies more broadly to communities rather than just nation-states. For African Americans, “defense” has always meant multiple forms of power and protection: economic self-sufficiency, political representation, educational excellence, cultural preservation, and yes, the ability to physically protect one’s community.

Economic Defense: The systematic destruction of Black economic power has been one of the most effective forms of subjugation in American history. From the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, where one of the nation’s most prosperous Black communities was literally bombed from the air and burned to the ground, to the countless other incidents of “Black Wall Streets” being destroyed across the country, the lesson is clear—economic vulnerability invites exploitation and attack.

Today, the racial wealth gap stands as a testament to ongoing economic vulnerability. The median white family has roughly ten times the wealth of the median Black family. This isn’t just about income; it’s about the accumulated resources that provide security, opportunity, and the ability to weather crises. Economic weakness leaves communities vulnerable to displacement through gentrification, exploitation through predatory lending, and the inability to build generational wealth.

Political Defense: The right to vote—and the protection of that right—represents a form of defense that Black Americans have had to fight for repeatedly. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was a defensive measure, protecting communities from the subjugation of political powerlessness. Its recent weakening has led to a resurgence of voter suppression tactics that leave Black communities vulnerable to policies and politicians that do not serve their interests.

Political power isn’t just about voting; it’s about representation at every level of government, from school boards to Congress. It’s about having prosecutors, judges, and law enforcement that reflect and protect the community rather than police it as an occupying force.

Educational Defense: Frederick Douglass understood that “knowledge makes a man unfit to be a slave.” The historical prohibition on Black literacy and the ongoing struggles for educational equity represent an understanding that an educated community is a defended community. Education provides the tools to recognize manipulation, to organize effectively, to access economic opportunities, and to preserve and advance culture and knowledge.

The persistent achievement gaps, school-to-prison pipeline, and under-resourcing of schools serving Black communities represent a continued vulnerability—one that limits future generations’ capacity for self-determination.

Chief Marshal Singh specifically warned that weakness invites subjugation, citing Venezuela as an example. For African Americans, history provides numerous examples of what happens when communities lack the various forms of power needed for self-defense.

The Wilmington Massacre of 1898 stands as a stark example. A thriving, politically empowered Black community in North Carolina was systematically destroyed by white supremacists in what was essentially a coup. The Black community’s relative weakness in arms, combined with the absence of federal protection, led to the murder of dozens (some estimates say hundreds), the destruction of property, and the exile of political leaders. The subjugation that followed lasted generations.

Conversely, there are examples of what happens when communities do have the means of defense. During the civil rights movement, the Deacons for Defense and Justice in Louisiana provided armed protection for civil rights workers and Black communities. While the mainstream civil rights narrative often emphasizes nonviolence exclusively, historians increasingly recognize that armed self-defense played a crucial role in protecting activists and deterring violence.

Robert F. Williams in Monroe, North Carolina demonstrated that when Black communities were willing and able to defend themselves, even the Ku Klux Klan thought twice about attacks. His advocacy for “armed self-reliance” alongside the struggle for civil rights represented an understanding that vulnerability invites aggression.

Today’s forms of subjugation are often more subtle than armed occupation, but they’re no less real. They come in the form of mass incarceration, which has removed millions of Black men and women from their communities. They come through environmental racism, where Black communities are disproportionately exposed to pollution and toxins. They come through food deserts, medical deserts, and banking deserts that leave communities vulnerable to poor health, limited options, and economic exploitation.

Criminal Justice as Occupation: The over-policing and mass incarceration of Black communities represents a form of internal subjugation. When a community’s young people are systematically removed and imprisoned at rates vastly disproportionate to their population, that community is weakened and vulnerable. The inability to protect one’s children from a system that treats them as criminals by default represents a profound form of defensive weakness.

Health as Defense: The COVID-19 pandemic starkly illustrated how health vulnerabilities leave communities open to disproportionate suffering. Black Americans died at significantly higher rates, reflecting underlying health disparities, limited access to quality healthcare, and economic circumstances that forced exposure. A community that cannot protect its health is vulnerable to decimation during crises.

Digital Defense: In the information age, the inability to control narratives, protect data privacy, and ensure equitable access to technology represents a new form of vulnerability. When algorithms discriminate, when communities lack broadband access, when Big Tech companies harvest data without consent, these represent forms of exploitation enabled by defensive weakness in the digital realm.

So what does the IAF chief’s warning mean in practical terms for Black America? It means that building comprehensive strength—economic, political, educational, cultural, and yes, even the capacity for physical self-defense—remains essential to avoiding subjugation.

Economic Empowerment: Supporting Black-owned businesses, building cooperative economic structures, promoting financial literacy, and creating investment vehicles that keep wealth circulating within the community. Organizations like Operation HOPE and the work of individuals like Killer Mike with Greenwood Bank represent efforts to build economic defense.

Political Organization: Sustained engagement in politics at every level, strategic coalition building, and the recognition that political power is defensive power. The work of organizations like Black Voters Matter and the continued fight for voting rights represent essential defensive measures.

Educational Excellence: Investment in HBCUs, support for educational equity, and the creation of alternative educational pathways that ensure young people have the knowledge and skills to navigate and shape their world.

Cultural Preservation: The maintenance of cultural identity, historical memory, and community bonds that cannot be easily broken or co-opted. A people without culture and history are more easily subjected to others’ narratives and control.

Self-Reliance Without Isolation: Building capacity for self-defense doesn’t mean separatism or refusing alliances. It means ensuring that the community has its own resources and capabilities so that it negotiates from strength rather than dependency.

When Air Chief Marshal AP Singh warned that weakness invites subjugation, he articulated a principle that African Americans have learned repeatedly throughout history. Every period of significant Black progress in America has been characterized by some combination of economic strength, political power, educational achievement, and the capacity for self-defense. Conversely, periods of regression have followed the weakening of these defenses.

The lesson isn’t about militarism or aggression—it’s about ensuring that communities have the various forms of power necessary to protect their interests, resist exploitation, and determine their own futures. A strong defense, in all its forms, doesn’t guarantee freedom from all challenges, but weakness virtually guarantees vulnerability to subjugation.

For Black America in 2026, this historical understanding means continuing the work of building power in all its dimensions. It means recognizing that strength and self-determination are not given but built, generation after generation, through sustained effort and strategic thinking. It means understanding that the alternative to building this strength isn’t simply stagnation—it’s vulnerability to forms of subjugation that may be more subtle than slavery or Jim Crow, but remain fundamentally about who has the power to shape their own destiny and protect their own interests.

The work of building comprehensive community defense is neither quick nor easy. It requires vision that extends beyond immediate crises to long-term capacity building. It requires coordination across different sectors and forms of power. It requires both pride in what has been accomplished and honest assessment of remaining vulnerabilities. It requires learning from history while adapting strategies to contemporary challenges. Most fundamentally, it requires rejecting the notion that any community should have to depend entirely on the goodwill of others for its safety, prosperity, and freedom.

The IAF chief’s warning, delivered halfway around the world in a different context, nonetheless speaks a truth that resonates across borders and through history: strength matters, weakness invites exploitation, and the price of inadequate defense is measured in freedom lost. For African Americans, this isn’t abstract theory but lived experience spanning centuries. The challenge now is to apply these hard-won lessons to building the comprehensive strength—economic, political, educational, cultural, and protective—necessary to ensure that future generations face a world where their community can defend its interests, protect its members, and chart its own course. The alternative, as both history and Chief Marshal Singh remind us, is vulnerability to subjugation in whatever form it takes in each new era.