Support the HBCU Library Alliance.

“Every book we keep on the shelf is a declaration that our stories, our truths, and our imaginations matter. To remove them is to erase the map of who we are.” — Audrey Wilson-Youngblood

In an era when the legitimacy of truth itself is being eroded, libraries once the unquestioned temples of knowledge have become contested ground. The modern attack on libraries is not only cultural but institutional, aimed at weakening public access to information, dismantling intellectual infrastructure, and isolating communities from the tools of collective understanding. For African America, and especially the HBCU ecosystem, this is not a distant concern it is a direct challenge to the long-standing relationship between literacy, liberation, and institutional survival. The current wave of book bans, funding cuts, and politicized library closures represents a deeper assault on the idea that the public has a right to know. And it is in this environment that HBCU libraries, public and private, must reimagine their mission, not just as archives of Black intellectual history, but as bulwarks in the defense of truth itself.

For generations, African American institutions have had to build and protect spaces for knowledge under siege. During Reconstruction and Jim Crow, when Black education was seen as subversive, libraries attached to Black colleges, churches, and fraternal lodges served as sanctuaries for books and people alike. They preserved history, trained minds, and sustained the belief that knowledge could be both shield and sword. Today, those same forces of suppression have reemerged in a more sophisticated form, algorithms replacing mobs, legislative bans replacing burned shelves, and digital manipulation replacing outright illiteracy. The struggle for knowledge remains the same: who controls it, who accesses it, and who benefits from it.

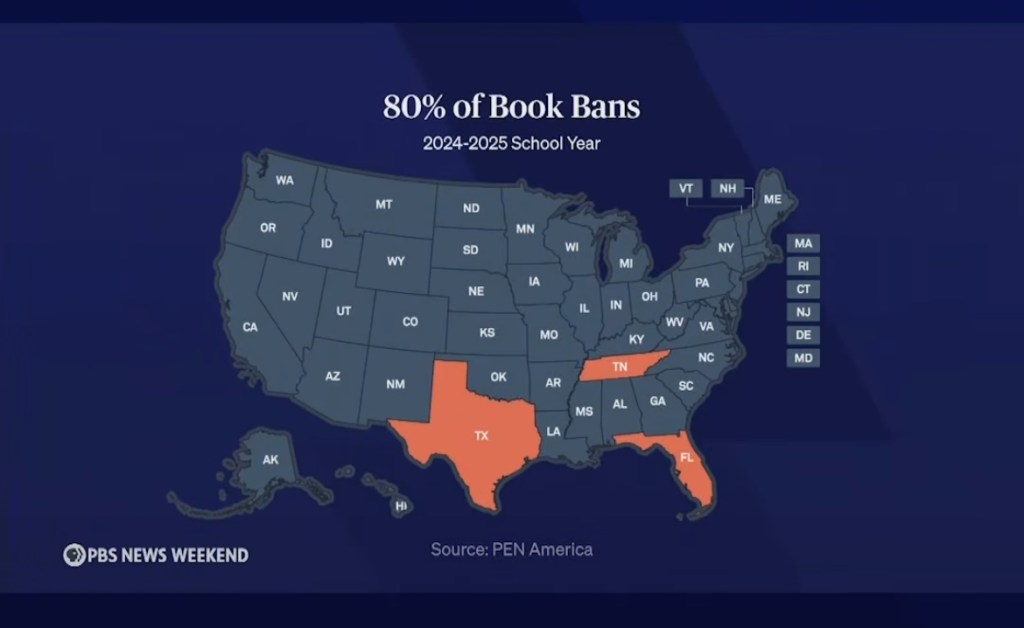

Quantitative Overview

- Total Bans (2024–2025 School Year): Over 6,800 book bans in U.S. public schools.

- Geographic Concentration: 80% of all bans occurred in just three states — Florida, Texas, and Tennessee.

- Source: PEN America, a nonprofit focused on literature and human rights, which tracks book bans and censorship trends nationwide.

HBCU libraries occupy a rare position in this struggle. They are simultaneously public institutions serving local communities and private guardians of African America’s most valuable intellectual assets. This dual nature offers both opportunity and obligation. Public HBCU libraries, especially those attached to state systems like North Carolina A&T, Florida A&M, and Prairie View A&M stand as extensions of the public’s right to access information. Yet they are increasingly forced to defend their collections, their autonomy, and their budgets against political interference. As states defund education or push ideological oversight into universities, HBCU libraries face a triple bind: underfunded by the state, underprotected by their parent institutions, and underrecognized by the very public they serve.

Private HBCU libraries, on the other hand, have greater flexibility and thus greater potential to lead a cultural counteroffensive. Institutions like Howard, Hampton, and Fisk hold rare manuscripts, archives, and collections that document the full arc of Black thought from enslavement to modernity. With proper public support and philanthropy, these libraries could transform themselves into the intellectual equivalent of fortified cities. Imagine a network of digitally integrated private HBCU libraries providing free, verifiable information to communities cut off from fair access by political manipulation. In a time when public libraries are being starved, private Black institutions could fill the void, becoming the last line of defense between ignorance and empowerment.

That future, however, demands preparation. HBCU libraries must begin treating their holdings not merely as academic resources but as national security assets for African America. The battle over information has moved from the classroom to the cloud, from debates about curriculum to the very algorithms that shape public thought. When AI-generated misinformation can rewrite history, when state legislatures can ban the discussion of race, and when digital archives can be quietly erased or altered, the traditional idea of a library must expand beyond shelves and catalogues. HBCU libraries should be building secure digital repositories, training students in archival cybersecurity, and creating decentralized backups that ensure African American intellectual heritage cannot be deleted by political fiat or corporate policy.

The institutional memory held within these libraries is irreplaceable. From microfilm records of Reconstruction newspapers to the papers of civil rights leaders, they embody a living history that still informs how African America defines itself and negotiates power. As new battles emerge over how history is taught and whose voices are validated, the role of these archives grows more urgent. Every document preserved, every oral history digitized, every banned book housed becomes a quiet act of resistance. Public libraries may be defunded; school curricula may be rewritten. But as long as these institutions endure, the truth remains findable.

The public has a role in this fight too. For too long, the African American community has viewed HBCU libraries as resources for students and scholars, rather than as public assets to be defended and used. That perception must change. If public libraries become political casualties, private and university-affiliated libraries may become the only trusted access points for research, reading, and civic education. The broader public of families, small businesses, advocacy groups should begin forging partnerships with these libraries now. Community reading programs, adult literacy drives, archival internships, and digital education workshops can all serve to widen the circle of ownership and support. The library must once again become what it was in the early twentieth century: a center of collective consciousness, not merely a study space.

For public HBCU libraries, the challenge is even more complex. Their funding is tied to state legislatures that may not share their mission or values. Preparing for this environment requires both political and institutional strategy. Libraries should diversify their revenue streams through alumni giving, research grants, and community endowments. They must also strengthen their advocacy infrastructure, ensuring that every legislative attack on curriculum or funding meets an organized, data-backed response. This is not simply about budgets it is about African American institutional sovereignty. A library that cannot defend its autonomy cannot defend its truth.

Digitization offers both opportunity and danger. While online archives can make information widely accessible, they also expose that information to censorship, manipulation, and control. Therefore, HBCU libraries must lead in developing secure, independently hosted knowledge systems. They should collaborate across institutions to form a “Black Knowledge Cloud,” a distributed digital archive that houses scanned materials from every HBCU library, protected by encryption and redundancy. Such a network could guarantee that if one institution’s system is compromised or defunded, the collective archive survives elsewhere. In this way, information becomes not only decentralized but immortal.

To fight back effectively, HBCU libraries must also think politically about technology. The rise of AI offers both peril and potential. AI can help catalog massive archives, identify patterns in historical documents, and expand public access but it can also reproduce bias, distort history, and replace human discernment with algorithmic opacity. HBCUs should develop their own AI literacy programs specifically for library science and archival management. Controlling how AI interacts with Black archives is not just a technical issue; it is a matter of cultural sovereignty. If we allow others to train their systems on our intellectual heritage without oversight, we risk losing ownership of our own story.

There is also a financial dimension to this battle. The survival of HBCU libraries cannot depend solely on institutional budgets or unpredictable philanthropy. They must create endowment-backed library trusts, investment funds, and public-private partnerships that treat knowledge as capital—something to be preserved and grown, not merely spent. Every rare manuscript, every research collection, every digital archive is a form of intellectual equity that must be protected with the same seriousness as real estate or securities. The wealth gap between predominantly white universities and HBCUs is mirrored in their libraries; reversing that imbalance requires intentional economic strategy. Knowledge without capital is vulnerable; capital without knowledge is blind.

In the end, the defense of HBCU libraries is about more than books. It is about control over narrative, truth, and power. In a society where disinformation spreads faster than literacy and where political actors can erase entire histories with the stroke of a legislative pen, libraries become the last democratic institution still capable of grounding reality. The fight for them is, therefore, a fight for the public’s right to exist as informed citizens rather than managed subjects. It is a fight that requires strategy, funding, solidarity, and imagination.

If African America is to withstand the coming storms of political revisionism and digital manipulation, it must understand that the next great battleground for freedom is not only in the courts or the streets it is in the archives. Every library that remains open, every catalog that stays accurate, every collection that endures represents a small victory in the war for truth. The question is whether the community will recognize that before it is too late.

HBCU libraries, both public and private, stand at the crossroads of history and strategy. They have the capacity to be both sanctuaries and fortresses, spaces where knowledge is preserved and from which it can be deployed. They can teach the public to fight back not with slogans, but with facts; not with outrage, but with understanding. In a world increasingly hostile to truth, they may become the last place where truth can still defend itself.

The Library as a Battlefield

In The Librarians, the PBS documentary referenced in the report, school librarians describe the toll of censorship battles, professional isolation, harassment, even job loss. These are not abstract debates. They are real human costs paid by those who refuse to compromise the intellectual rights of children.

The same courage will be demanded of HBCU librarians. They must understand that they, too, are combatants in an intellectual war, not merely caretakers of catalogues. The stakes are not just academic, they are civilizational.

Building an Infrastructure of Freedom

To do this, HBCUs will need resources and strategy. Here are several paths forward:

- The Banned Book Consortium:

HBCUs could collectively form a digital repository housing every banned or challenged title. This archive would not only preserve literature but would also serve as a research tool for scholars studying censorship, education, and democracy. - Freedom Librarian Fellowships:

Create fellowships for librarians and archivists to train in censorship resistance, digital preservation, and public engagement—transforming librarianship into an instrument of civil defense. - Community Literacy Partnerships:

Partner with local school districts and community centers to host banned book reading programs, public forums, and educational events. Even in restrictive states, these partnerships can exist off-campus or through nonprofit intermediaries. - Legal and Policy Advocacy:

Leverage HBCU law schools, journalism programs, and public policy centers to provide legal research and public testimony on the effects of educational censorship. - Endowments for Intellectual Independence:

Philanthropy and Black wealth should prioritize library endowments at HBCUs. An independent funding base ensures these institutions can act without political interference.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.