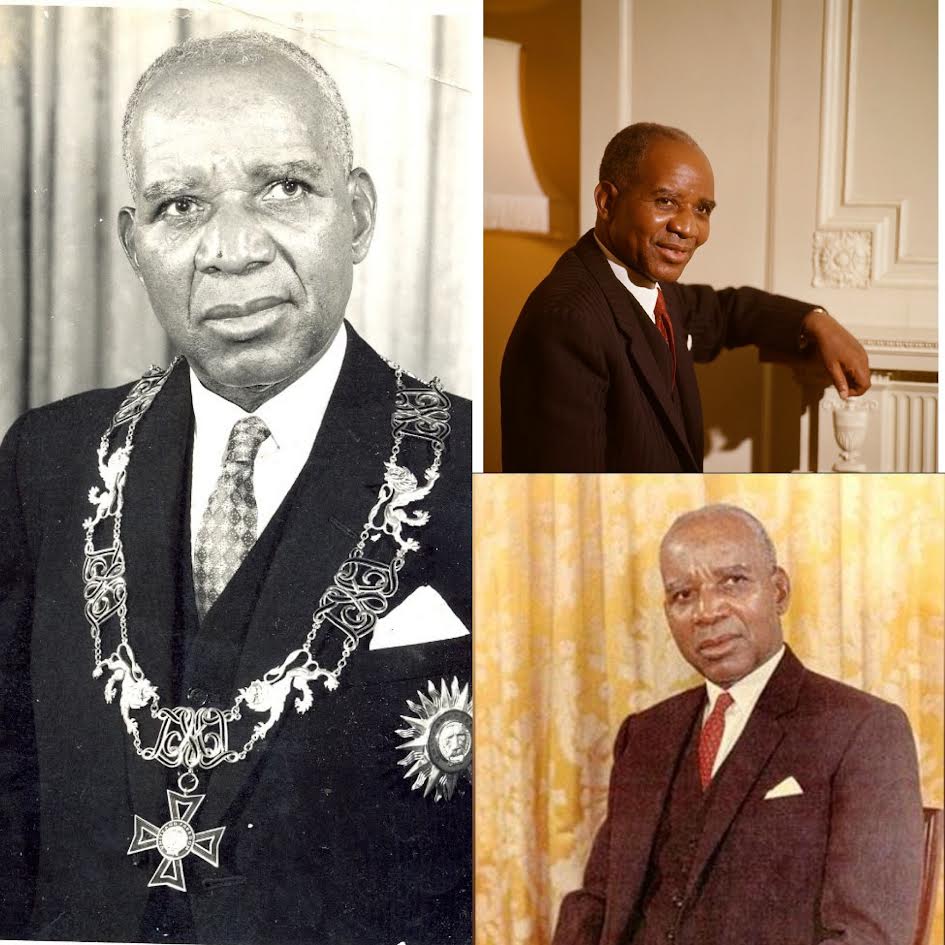

In the historic halls of Central State University and the rigorous lecture rooms of Meharry Medical College, a young African student once walked with a dream—not merely of medicine, but of freedom. That student was Hastings Kamuzu Banda, the man who would one day become the founding president of the Republic of Malawi.

His story is rarely told from an HBCU lens. Yet, it is precisely the experience at two Historically Black Colleges and Universities—Central State University in Ohio and Meharry Medical College in Tennessee—that laid the intellectual, political, and moral groundwork for his eventual campaign to end British colonial rule in Nyasaland.

In the present-day debate about HBCUs’ global relevance, Banda’s journey stands as a compelling argument that these institutions have not only nurtured African American leadership but also shaped African sovereignty.

A Midwestern Genesis: Central State’s Early Influence

Before there was a “Dr. Banda,” there was a young African migrant named Hastings who arrived in the United States during the late 1920s. He enrolled at what is now Central State University, then a part of Wilberforce University and a beacon for Black education in the Midwest.

It was at Central State that Banda was introduced to the dual power of higher learning and Pan-African identity. He encountered professors who taught from both the Western canon and African nationalist traditions. He lived among African Americans who were part of the Great Migration and had firsthand experience with economic and racial disenfranchisement. The cultural cross-pollination at Central State expanded his worldview and rooted his developing philosophy in Black resilience.

Though he would later transfer to the University of Chicago for further undergraduate studies, Central State gave him more than academic credit—it gave him credibility in Black political thought.

A Different Kind of Medical School: Meharry and the Making of a Leader

Following his studies in Chicago, Banda attended Meharry Medical College, one of the most prominent Black medical institutions in the country. Graduating in 1937, Banda’s time at Meharry deeply influenced his worldview—not just about medicine, but about how institutions could serve and uplift Black people independently of white power structures.

Unlike predominantly white institutions that frequently isolated African and African American students, Meharry was fully Black-led and Black-centered. It was governed by African American trustees, taught by Black faculty, and embedded in the racial and political tensions of the Jim Crow South. For Banda, who had come from colonial Africa where no such institutional control existed, this was nothing short of transformative.

It was also profoundly Pan-African. At Meharry, Banda was exposed to debates around the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, the writings of W.E.B. Du Bois, and Marcus Garvey’s vision of African redemption. These ideological frameworks offered more than theory—they provided the intellectual blueprints for governance, sovereignty, and self-respect.

Diasporic Bridges: From HBCUs to Global Nation-Building

Central State gave Banda an academic introduction to the Black freedom struggle. Meharry gave him professional tools and the institutional example of what Black autonomy could look like. Together, they formed the crucible for his Pan-African nationalist evolution.

When Banda returned to Africa in 1958 after decades abroad, he was not just a foreign-trained doctor. He was an emissary of a very specific educational and political tradition—the HBCU tradition. This tradition emphasized:

- Service to Black communities

- Self-sufficiency through education

- Respectability as a political strategy

- Institutional sovereignty over assimilation

These values translated directly into his political project in Nyasaland. He became head of the Nyasaland African Congress, leading efforts against the British colonial federation and eventually negotiating the country’s peaceful transition to independence in 1964.

In a continent where many leaders were educated in European universities, Banda stood out. His fluency in African American political culture made him a bridge between the African continent and its Diaspora, especially in Washington, D.C., where his HBCU pedigree was a diplomatic asset in U.S. foreign policy circles.

The Paradox of the HBCU-Trained Autocrat

But the story of Banda’s legacy is not without tension.

While his education gave him the language of freedom, it also ingrained in him a conservative framework that emphasized discipline, hierarchy, and moralism. At Central State and Meharry, institutions that demanded decorum in the face of oppression, Banda saw how strict codes of conduct were used as a survival mechanism. Later, as President-for-Life of Malawi, he applied these methods ruthlessly.

Under Banda, political opposition was outlawed, newspapers were censored, and a cult of personality was cultivated. Public displays of affection were banned. Women were forbidden to wear trousers. The Malawi Young Pioneers, a paramilitary wing of his ruling party, became infamous for quashing dissent.

These tendencies—while not direct exports of HBCU education—reflected a misapplication of the values of institutional discipline and order that had once empowered him.

Reclaiming the Global HBCU Legacy

In today’s global higher education discourse, the international impact of HBCUs is often underplayed. Yet Banda’s journey from Central State to Meharry to Malawi’s presidency proves that these institutions were once central players in African decolonization.

- Central State trained his political consciousness.

- Meharry trained his professional discipline.

- Both trained his belief in Black institutional capacity.

Rather than being purely domestic engines of uplift, HBCUs once served as global academies of Black leadership. The African continent remembers that—even if America has forgotten.

This legacy calls for intentional reclamation. HBCUs must reimagine their diplomatic role: building African partnerships, recruiting international students, and positioning themselves not just as institutions of higher education—but as instruments of geopolitical influence.

Closing Reflection: Banda, Central State, and Meharry in Retrospect

Hastings Banda is a complicated icon. He ushered in national independence but also ruled as a strongman. He built schools and hospitals but suppressed journalists and dissenters. He praised discipline but punished freedom.

Still, from an HBCU perspective, he offers a rare case study of transnational Black education at work. Few institutions in the world can claim that their alumni overthrew colonial empires and established new nations.

Central State University can.

Meharry Medical College can.

And for today’s HBCU community, that is not just a point of pride—it is a point of power.

Sidebar: Timeline of Hastings Banda’s HBCU Journey

- 1920s – Enrolled at Central State University (then affiliated with Wilberforce University)

- 1930 – Graduated from the University of Chicago

- 1934–1937 – Attended Meharry Medical College

- 1958 – Returned to Nyasaland to lead anti-colonial movement

- 1964 – Became Prime Minister of independent Malawi

- 1971 – Declared President-for-Life

- 1994 – Lost multiparty elections, retired from politics

- 1997 – Died in Johannesburg, South Africa